Difference between revisions of "Exe0.2 Molly Schwartz"

| (10 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Seductive Conversions: Experience the Difference''' | |||

| Line 7: | Line 6: | ||

Moments of conversion from one way of thinking to another are mysterious, yet they are essential to human existence. At times fluid, at other times torturous, conversions are brought about by factors that are variable and unpredictable. Although there are certainly trends and techniques, there are no universal laws for leading people to think otherwise than they did before. Yet human societies are built upon consensus, which makes conversions necessary. I would argue that creating moments for people to experience a familiar thing in a new way, thereby paving the way moments of conversion and consensus, is the ultimate purpose of media and art. | Moments of conversion from one way of thinking to another are mysterious, yet they are essential to human existence. At times fluid, at other times torturous, conversions are brought about by factors that are variable and unpredictable. Although there are certainly trends and techniques, there are no universal laws for leading people to think otherwise than they did before. Yet human societies are built upon consensus, which makes conversions necessary. I would argue that creating moments for people to experience a familiar thing in a new way, thereby paving the way moments of conversion and consensus, is the ultimate purpose of media and art. | ||

Inspired by the idea that literary fiction is a way to knowledge (Hemer 2012:30) and through the framework of Gilles Deleuze’s philosophy of becoming (Deleuze 1995), this installation will explore the ways in which works of fiction, and particularly speculative fiction, play with experiences that are false and unknowable in order to express and facilitate moments of seeing things in a new light | Inspired by the idea that literary fiction is a way to knowledge (Hemer 2012:30) and through the framework of Gilles Deleuze’s philosophy of becoming (Deleuze 1995), this installation will explore the ways in which works of fiction, and particularly speculative fiction, play with experiences that are false and unknowable in order to express and facilitate moments of seeing things in a new light. The installation would lead viewers through a multimodal experience of an excerpt from ''Submission'', Michel Houellebecq’s work of speculative fiction, in which Houellebecq’s protagonist has one in a series of encounters with a foreign way of life that ultimately lead to his conversion to Islam. Far from a mystical experience, Houellebecq creates a banal conversion experience that achieves cognitive estrangement through physical seduction. | ||

| Line 26: | Line 25: | ||

The world of Houellebecq’s François in bears fairly close resemblance to modern-day Paris: François rides the TGV, watches YouPorn, works on a laptop, smokes cigarettes, orders take-out sushi, and Marine Le Pen is the president of the National Front party. Without employing any grandiose reality-warping tricks, Houellebecq proceeds in the course of 256 pages to erode two of the fundamental building blocks of modern-day French society: secularism and equal rights for women. So, how does Houellebecq create an experience with the reader in which the democratic adoption of Sharia law in France seem authentic, plausible, and even desirable? Rather than jolting the narrative to a level of cognitive estrangement that by defamliarizing the mundane, Houellebecq builds the narrative on top of descriptions of the mundane, trivial, materialistic pleasures of modern consumer culture. In this way he lulls, or seduces, participants in the narrative to accept an unlikely scenario as both a possible future and a reflection on present realities. | The world of Houellebecq’s François in bears fairly close resemblance to modern-day Paris: François rides the TGV, watches YouPorn, works on a laptop, smokes cigarettes, orders take-out sushi, and Marine Le Pen is the president of the National Front party. Without employing any grandiose reality-warping tricks, Houellebecq proceeds in the course of 256 pages to erode two of the fundamental building blocks of modern-day French society: secularism and equal rights for women. So, how does Houellebecq create an experience with the reader in which the democratic adoption of Sharia law in France seem authentic, plausible, and even desirable? Rather than jolting the narrative to a level of cognitive estrangement that by defamliarizing the mundane, Houellebecq builds the narrative on top of descriptions of the mundane, trivial, materialistic pleasures of modern consumer culture. In this way he lulls, or seduces, participants in the narrative to accept an unlikely scenario as both a possible future and a reflection on present realities. | ||

Which opens the question: if the meaning of literature lies in the experience of it, in the process of reading and writing, then does speculative fiction operate more like functional code or test code when it is "executed"? According to Kent Beck, a well-known software developer and who outlined the principles and practices of Test-Driven Development (TDD) in his book ''Test-Driven Development: By Example'' (2002), software developers should spend at least 25-50% of their time writing test code that runs in tandem with functional code (at a ratio of about three to one). ''Submission'' runs in reaction and in parallel to our current state of affairs, shining a light on potential points of failure to come. | Which opens the question: if the meaning of literature lies in the experience of it, in the process of reading and writing, then does speculative fiction operate more like functional code or test code when it is "executed"? According to Kent Beck, a well-known software developer and who outlined the principles and practices of Test-Driven Development (TDD) in his book ''Test-Driven Development: By Example'' (2002), software developers should spend at least 25-50% of their time writing test code that runs in tandem with functional code (at a ratio of about three to one). In a world saturated by software and its accompanying bugs and errors, a tremendous amount of resources is dedicated to predicting and averting points of failure. Speculative fictions serve as portenders of things to come as they weave into the imaginaries and enactments of future presents (Dourish & Bell 2014). ''Submission'' runs in reaction and in parallel to our current state of affairs, shining a light on potential points of failure to come. Therefore, in the pragmatist tradition of analyzing literature, not in terms of whether it is "true" or "accurate" but in terms of "what it does" (Wood 1996:12), I look at speculative fiction and Houellebecq's novel as a combination of functional and test code, both the mirror and the caution sign. | ||

Houellebecq | In an eery turn of events, ''Submission'' was published in France on January 7, 2015, the same day as the Charlie Hebdo shooting, in which Islamist terrorists killed 12 people in the magazines Paris offices. The issue of Charlie Hebdo that was published just before the massacre featured a full-cover satiric cartoon of Michel Houellebecq under the headline, "The Predictions of Wizard Houellebecq." With fatwas being issued on authors' heads and the rise of Donald Trump's presidential campaign on the platform of banning Muslims from entering the United States, ''Submission'' presents a strong case for analyzing speculative fiction as operational media. | ||

====Interactive Installation==== | |||

====Interactive Installation==== | |||

My installation is intended to create a multimodal experience that dives into one of the scenes in Submission when we experience an alternative reality in which women have lost all autonomy and are permanently submissive to men, yet we perceive how this state of affairs could be beneficial for both men and women. The installation is meant to question the generative nature of narratives and the feedback loop between writer and reader by alternatively decoupling and reuniting images of events in the novel from their corresponding text. | My installation is intended to create a multimodal experience that dives into one of the scenes in Submission when we experience an alternative reality in which women have lost all autonomy and are permanently submissive to men, yet we perceive how this state of affairs could be beneficial for both men and women. The installation is meant to question the generative nature of narratives and the feedback loop between writer and reader by alternatively decoupling and reuniting images of events in the novel from their corresponding text. | ||

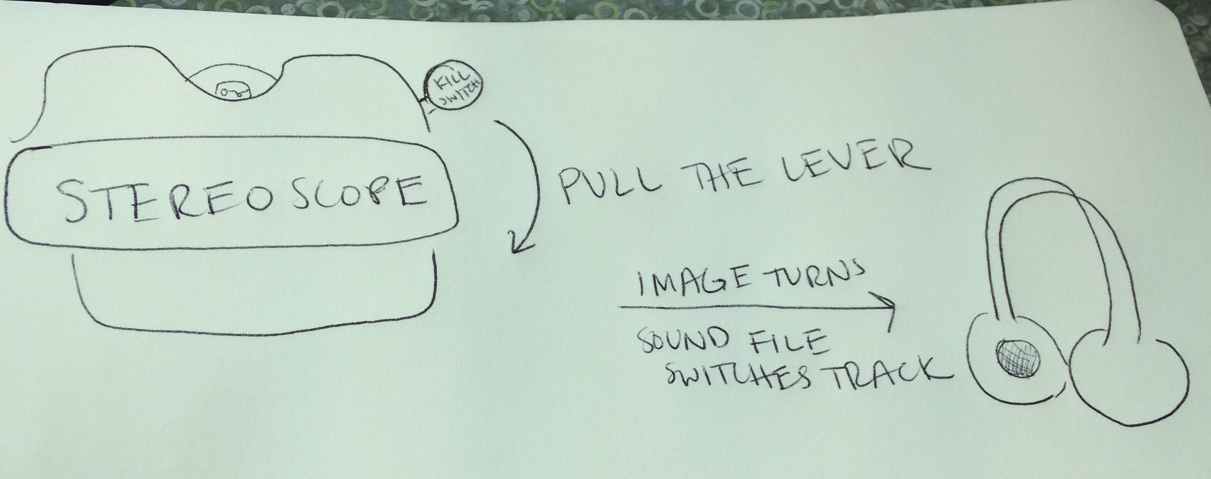

First, you hold up a 3-D View-Master stereoscope to your eyes and put on a pair of headphones. The headphones are connected to a laptop with three sound files open that alternate randomly on shuffle. The stereoscope contains a reel of seven images that illustrate the events in a scene from Submission. | First, you hold up a 3-D View-Master stereoscope to your eyes and put on a pair of headphones. The headphones are connected to a laptop with three sound files open that alternate randomly on shuffle. The stereoscope contains a reel of seven images that illustrate the events in a scene from Submission. | ||

[[File:stereoscope.jpg]] | |||

Participants press play to start the sound file and then look into the stereoscope at the first image. After the first track of the sound track comes to an end, participants flip the switch on the stereoscope (also known as "dropping the guillotine”). The switch is connected to an Arduino microcomputer that has been programmed to move to the next soundtrack when the stereoscope switch is flipped. Therefore, participants will listen to text that corresponds with each of the seven images that they view. | Participants press play to start the sound file and then look into the stereoscope at the first image. After the first track of the sound track comes to an end, participants flip the switch on the stereoscope (also known as "dropping the guillotine”). The switch is connected to an Arduino microcomputer that has been programmed to move to the next soundtrack when the stereoscope switch is flipped. Therefore, participants will listen to text that corresponds with each of the seven images that they view. | ||

[[File:prototype.jpg]] | |||

Content of images: | Content of images: | ||

Image 1: François in a seat on the TGV by himself holding a newspaper, looking at the party sitting across the aisle | *Image 1: François in a seat on the TGV by himself holding a newspaper, looking at the party sitting across the aisle | ||

Image 2: Arab businessman in long white djellaba and a white keffiyeh sitting in front of two tables, two young girls in their teens wearing long robes and multi-colored veils sitting across the aisle from François. There are files spread out across the tables in front of the businessman. One girl is reading a Picsou comic and giggling, the is reading the latest issue of Oops magazine. Candy bars sit on the tables in front of the girls. | *Image 2: Arab businessman in long white djellaba and a white keffiyeh sitting in front of two tables, two young girls in their teens wearing long robes and multi-colored veils sitting across the aisle from François. There are files spread out across the tables in front of the businessman. One girl is reading a Picsou comic and giggling, the other is reading the latest issue of Oops magazine. Candy bars sit on the tables in front of the girls. | ||

Image 3: Looking over the businessman’s shoulder. He has his emails and spreadsheets open on his computer. He is making a call on his cell phone. A side-long shot at his face shows that he is busy and stressed. | *Image 3: Looking over the businessman’s shoulder. He has his emails and spreadsheets open on his computer. He is making a call on his cell phone. A side-long shot at his face shows that he is busy and stressed. | ||

Image 4: François tries to return to reading his newspaper | *Image 4: François tries to return to reading his newspaper | ||

Image 5: The two young Arab girls are giggling to each other and pointing at the copy of Picsou while the businessman looks at them with a tense smile, still on his cell phone | *Image 5: The two young Arab girls are giggling to each other and pointing at the copy of Picsou while the businessman looks at them with a tense smile, still on his cell phone | ||

Image 6: Over-the-shoulder shot of the two girls, heads together, whispering happily to each other and giggling. We see their magazines and candy littered over the table in front of them. | *Image 6: Over-the-shoulder shot of the two girls, heads together, whispering happily to each other and giggling. We see their magazines and candy littered over the table in front of them. | ||

Image 7: Full screen shot of François’ face, lost in thought | *Image 7: Full screen shot of François’ face, lost in thought | ||

The disorienting feature is that participants will listen to one of three sound files. One sound files is an audio recording of the text from Submission, so the participant will listen to the text of the novel while looking at a visual illustration of the scene. One sound file is an audio recording of an excerpt from Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace in which a main character, Prince Andrei, undergoes a conversion experience that is manifested in his reactions to an oak tree that his carriage drives by on the way to and from his destination. The third sound file is an audio recording of an excerpt from J.K. Huysmans’ À Rebours in which the protagonist, Des Esseintes, expresses the failings of nature in comparison to artifice and sensually describes the attractive physicality of locomotives. | The disorienting feature is that participants will listen to one of three sound files. One sound files is an audio recording of the text from ''Submission'', so the participant will listen to the text of the novel while looking at a visual illustration of the scene. One sound file is an audio recording of an excerpt from Leo Tolstoy’s ''War and Peace'' in which a main character, Prince Andrei, undergoes a conversion experience that is manifested in his reactions to an oak tree that his carriage drives by on the way to and from his destination. The third sound file is an audio recording of an excerpt from J.K. Huysmans’ ''À Rebours'' in which the protagonist, Des Esseintes, expresses the failings of nature in comparison to artifice and sensually describes the attractive physicality of locomotives. | ||

While the three textual excerpts have common themes and literary devices, such as rich imagery that defamiliarize us from familiar objects, the displacement of spiritual journeys into physical objects, elements of physical journeys through modes of man-made transportation, their pairings with the images will create three very different narrative experiences for the participants. Although the stereoscope and audio will be set up in such a way that participants have no control over the content that they experience (the images move linearly without a possibility of rewinding, the audio files are programmed to play at prescribed moments), this is only meant to highlight that the meaning of the same content lies in the participants’ experience of it. | While the three textual excerpts have common themes and literary devices, such as rich imagery that defamiliarize us from familiar objects, the displacement of spiritual journeys into physical objects, elements of physical journeys through modes of man-made transportation, their pairings with the images will create three very different narrative experiences for the participants. Although the stereoscope and audio will be set up in such a way that participants have no control over the content that they experience (the images move linearly without a possibility of rewinding, the audio files are programmed to play at prescribed moments), this is only meant to highlight that the meaning of the same content lies in the participants’ experience of it. | ||

Excerpt from Submission with corresponding images (pages 183-185): | '''Excerpt from ''Submission'' with corresponding images (pages 183-185):''' | ||

Image 1: I found a seat by myself, with no one across from me. Image 2: On the other side of the aisle a middle-aged Arab businessman, dressed in a long white djellaba and a white keffiyeh, had spread out several files on the two tables in front of his seat. He must have been coming from Bordeaux. There were two young girls facing him, barely out of their teens — his wives, clearly — who had raided the newsstand for candy and magazines. They were excited and giggly. They wore long robes and multicolored veils. For the moment, one was absorbed in a Picsou comic, the other in the latest issue of Oops. | Image 1: I found a seat by myself, with no one across from me. Image 2: On the other side of the aisle a middle-aged Arab businessman, dressed in a long white djellaba and a white keffiyeh, had spread out several files on the two tables in front of his seat. He must have been coming from Bordeaux. There were two young girls facing him, barely out of their teens — his wives, clearly — who had raided the newsstand for candy and magazines. They were excited and giggly. They wore long robes and multicolored veils. For the moment, one was absorbed in a Picsou comic, the other in the latest issue of Oops. | ||

Image 3: Across from them, the businessman looked as if he was under some serious stress. Opening his e-mail, he downloaded an attachment containing several Excel spreadsheets, and after examining these documents, he looks even more worried than before. He made a call on his cell phone. A long, hushed conversation ensued. Shot 4: It was impossible to tell what he was talking about, and I tried, without a great deal of enthusiasm, to get back to my Figaro, which covered the new regime from a real estate and luxury angle. From this point of view, the future was looking extremely bright. The subjects of the petromonarchies were more and more eager to pick up a pied-à-terre in Paris or on the Côte d’Azur, now that they knew they were dealing with a friendly country, and were outbidding the Chinese and the Russians. Business was good. | Image 3: Across from them, the businessman looked as if he was under some serious stress. Opening his e-mail, he downloaded an attachment containing several Excel spreadsheets, and after examining these documents, he looks even more worried than before. He made a call on his cell phone. A long, hushed conversation ensued. Shot 4: It was impossible to tell what he was talking about, and I tried, without a great deal of enthusiasm, to get back to my Figaro, which covered the new regime from a real estate and luxury angle. From this point of view, the future was looking extremely bright. The subjects of the petromonarchies were more and more eager to pick up a pied-à-terre in Paris or on the Côte d’Azur, now that they knew they were dealing with a friendly country, and were outbidding the Chinese and the Russians. Business was good. | ||

Image 5: Peals of laughter: the two young Arab girls were hunched over the copy of Picsou, playing “Spot the Difference.” Looking up from his spreadsheet, the businessman gave them a pained smile of reproach. They smiled back and went on playing, now in excited whispers. He took out his cell again and another conversation ensued, just as long and confidential as the first. Image 6: Under an Islamic regime, women — at least the ones pretty enough to attract a rich husband — were able to remain children nearly their entire lives. No sooner had they put childhood behind them than they became mothers and were plunged back into a world of childish things. Their children grew up, then they became grandmothers, and so their lives went by. There were just a few years where they bought sexy underwear, exchanging the games of the nursery for those of the bedroom — which turned out to be much the same thing. Image 7: Obviously they had no autonomy, but as they say in English, fuck autonomy. I had to admit, I’d no trouble giving up all of my professional and intellectual responsibilities, it was actually a relief, and I had no desire whatsoever to be that businessman sitting on the other side of our Pro Première compartment, whose face grew more and more ashen the longer he talked on the phone, and who was obviously in some kind of deep shit. Our train had just passed Saint-Pierre-des-Corps. At least he’d have the consolation of two graceful, charming wives to distract him from the anxieties facing the exhausted businessman — and maybe he had two more wives waiting for him in Paris. If I remembered right, according to sharia law you could have up to four. What had my father had? My mother, that neurotic bitch. I shuddered at the thought. Well, she was dead now. They were both dead. I might have seen better days, but I was the only living witness to their love. | |||

'''Excerpt from Huysmans’ ''À Rebours'' with corresponding images:''' | |||

Image 1: To tell the truth, artifice was in Des Esseintes' philosophy the distinctive mark of human genius. | Image 1: To tell the truth, artifice was in Des Esseintes' philosophy the distinctive mark of human genius. | ||

| Line 88: | Line 81: | ||

Image 7: Thoughts like these would come to Des Esseintes at times when the breeze carried to his ears the far-off whistle of the baby railroad that plies shuttlewise backwards and forwards between Paris and Sceaux. His house was within a twenty minutes' walk or so of the station of Fontenay, but the height at which it stood and its isolated situation left it entirely unaffected by the noise and turmoil of the vile hordes that are inevitably attracted on Sundays by the neighbourhood of a railway station. | Image 7: Thoughts like these would come to Des Esseintes at times when the breeze carried to his ears the far-off whistle of the baby railroad that plies shuttlewise backwards and forwards between Paris and Sceaux. His house was within a twenty minutes' walk or so of the station of Fontenay, but the height at which it stood and its isolated situation left it entirely unaffected by the noise and turmoil of the vile hordes that are inevitably attracted on Sundays by the neighbourhood of a railway station. | ||

Excerpt from Tolstoy’s War and Peace with corresponding images (pages 419-420): | '''Excerpt from Tolstoy’s ''War and Peace'' with corresponding images (pages 419-420):''' | ||

Image 1: At the side of the road stood an oak. Probably ten times older than the birches of the woods, it was ten times as thick and twice as tall as any birch. It was an enormous oak, twice the span of a man’s arm in girth, with some limbs broken off long ago, and broken bark covered with old scars. With its huge, gnarled, ungainly, unsymmetrically spread arms and fingers, it stood, old, angry, scornful, and ugly, amidst the smiling birches. It alone did not want to submit to the charm of spring and did not want to see either the springtime or the sun. | Image 1: At the side of the road stood an oak. Probably ten times older than the birches of the woods, it was ten times as thick and twice as tall as any birch. It was an enormous oak, twice the span of a man’s arm in girth, with some limbs broken off long ago, and broken bark covered with old scars. With its huge, gnarled, ungainly, unsymmetrically spread arms and fingers, it stood, old, angry, scornful, and ugly, amidst the smiling birches. It alone did not want to submit to the charm of spring and did not want to see either the springtime or the sun. | ||

| Line 94: | Line 87: | ||

Image 3: Prince Andrei turned several times to look at this oak as he drove through the woods, as if he expected something from it. There were flowers and grass beneath the oak as well, but it stood among them in the same way, scowling, motionless, ugly, and stubborn. | Image 3: Prince Andrei turned several times to look at this oak as he drove through the woods, as if he expected something from it. There were flowers and grass beneath the oak as well, but it stood among them in the same way, scowling, motionless, ugly, and stubborn. | ||

Image 4: “Yes, it’s right, a thousand times right, this oak,” thought Prince Andrei. “Let others, the young ones, succumb afresh to this deception, but we know life — our life is over!” A whole new series of thoughts in connection with the oak, hopeless but sadly pleasant, emerged in Prince Andrei’s soul. During this journey it was as if he again thought over his whole life and reached the same old comforting and hopeless conclusion, that there was no need for him to start anything, that he had to live out his life without doing evil, without anxiety, and without wishing for anything. | Image 4: “Yes, it’s right, a thousand times right, this oak,” thought Prince Andrei. “Let others, the young ones, succumb afresh to this deception, but we know life — our life is over!” A whole new series of thoughts in connection with the oak, hopeless but sadly pleasant, emerged in Prince Andrei’s soul. During this journey it was as if he again thought over his whole life and reached the same old comforting and hopeless conclusion, that there was no need for him to start anything, that he had to live out his life without doing evil, without anxiety, and without wishing for anything. | ||

Image 5: “Yes, here in this woods,was that oak that I agreed with,” thought Prince Andrei. “But where is it?” he thought again, looking at the left side of the road, and, not knowing it himself, not recognizing it, he admired the very oak he was looking for. The old oak, quite transformed, spreading out a canopy of juicy, dark greenery, basked, barely swaying, in the ray of the evening sun. Of the gnarled fingers, the scars, the old grief and mistrust — nothing could be seen. Juicy green leaves without branches broke through the stiff, hundred-year-old bark, and it was impossible to believe that this old fellow had produced them. Image 6: “Yes it’s the same oak,” thought Prince Andrei, and suddenly a causeless springtime feeling of joy and renewal came over him. All the best moments of his life suddenly recalled themselves to him at the same time. Austerlitz with the lofty sky, and the dead, reproachful face of his wife, and Pierre on the ferry, and a girl excited by the beauty of the night, and that night itself, and the moon — all of it suddenly recalled itself to him. Image 7: “No, life isn’t over at the age of thirty-one,” Prince Andrei suddenly decided definitively, immutably. “It’s not enough that I know all that’s in me, everyone else must know it, too: Pierre, and that girl who wanted to fly into the sky, everyone must know me, so that my life is not only for myself; so that they don’t live like that girl, independently of my life, but so that it is reflected in everyone, and they all live together with me!" | |||

Image 5: “Yes, here in this woods,was that oak that I agreed with,” thought Prince Andrei. “But where is it?” he thought again, looking at the left side of the road, and, not knowing it himself, not recognizing it, he admired the very oak he was looking for. The old oak, quite transformed, spreading out a canopy of juicy, dark greenery, basked, barely swaying, in the ray of the evening sun. Of the gnarled fingers, the scars, the old grief and mistrust — nothing could be seen. Juicy green leaves without branches broke through the stiff, hundred-year-old bark, and it was impossible to believe that this old fellow had produced them. Image 6: “Yes it’s the same oak,” thought Prince Andrei, and suddenly a causeless springtime feeling of joy and renewal came over him. All the best moments of his life suddenly recalled themselves to him at the same time. Austerlitz with the lofty sky, and the dead, reproachful face of his wife, and Pierre on the ferry, and a girl excited by the beauty of the night, and that night itself, and the moon — all of it suddenly recalled itself to him. | |||

====References==== | ====References==== | ||

Chun, W. (2004). "On Software, or the Persistence of Visual | Chun, W. (2004). "On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge”, in ''Grey Room'' 18, pp. 26–51 http://www.brown.edu/Departments/MCM/people/chun/papers/software.pdf | ||

Damarin, S. (2004). "Chapter Three: Required Reading: Feminist Sci-Fi and Post-Millennial Curriculum | Damarin, S. (2004). "Chapter Three: Required Reading: Feminist Sci-Fi and Post-Millennial Curriculum", in ''Counterpoints'' vol. 158, pp. 51-73 | ||

Deleuze, G. (1995). Negotiations, 1972–1990. New York: Columbia University Press | Deleuze, G. (1995). ''Negotiations, 1972–1990''. New York: Columbia University Press | ||

-------------- (1997). ''Essays critical and clinical.'' Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press | |||

-------------- (1994). ''Difference and Repetition''. Trans. Patton, P. New York, Columbia University Press | |||

Eizykman, B. (1975). "On Science Fiction", Trans. Fitting, P. in ''Science Fiction Studies'', vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 164-166 | |||

Review of | Bahti, T. (1993). "Review of Narrative Crossings: Theory and Pragmatics of Prose Fiction. By Alexander Gelley", in ''Comparative Literature'' vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 177-180 | ||

Dourish, P. and Bell, G. (2014). "Resistance is Futile": Reading Science Fiction Alongside Ubiquitous Computing.” in ''Personal and Ubiquitous Computing'' 18, 4, pp. 769-778. | |||

Galloway, A. (2004). ''Protocol: How Control Exists After Decentralization''. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press | |||

----------- (2013) "The Poverty of Philosophy: Realism and Post-Fordism", in ''Critical Inquiry'', vol. 39, no. 2 pp. 347-366 | |||

Gordon, J. "Gazing across the Abyss: The Amborg Gaze in Sheri S. Tepper's "Six Moon Dance" Author(s): Joan Gordon Source: Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 35, No. 2, On Animals and Science Fiction (Jul., 2008), pp. 189-206 Published by: SF-TH Inc Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25475138 Accessed: 13-04-2016 13:24 UTC | |||

Grimstad, P. (2013). ''Experience and Experimental Writing: Literary Pragmatism from Emerson to the Jameses''. Oxford: Oxford University Press | |||

Hayles, N. K. (2008). ''Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary''. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame | |||

Hemer, O. (2012). ''Fiction and Truth in Transition: Writing the present past in South Africa and Argentina''. Zürich: LIT VERLAG GmbH & Co. KG Wien | |||

Houellebecq, M. (2015). ''Submission: A Novel''. Trans. Stein, L. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux | |||

Jameson, F. (2005). ''Archaeologies of the future, the desire called utopia and other science fictions''. London: Verso | |||

Whitehead, A. (1955). Adventures of Ideas. A Mentor Book. | Whitehead, A. (1955). Adventures of Ideas. A Mentor Book. | ||

Wood, B. ( | Wood, B. (1996). "William S. Burroughs and the Language of Cyberpunk”, in ''Science Fiction Studies'' vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 11-26 | ||

Zepke, S. ( | Zepke, S. (2012). "Beyond cognitive estrangement: The future of science fiction cinema”, in ''NECSUS: European Journal of Media Studies'' http://www.necsus-ejms.org/beyond-cognitive-estrangement-the-future-of-science-fiction-cinema/ | ||

Latest revision as of 20:48, 27 April 2016

Seductive Conversions: Experience the Difference

Abstract

Moments of conversion from one way of thinking to another are mysterious, yet they are essential to human existence. At times fluid, at other times torturous, conversions are brought about by factors that are variable and unpredictable. Although there are certainly trends and techniques, there are no universal laws for leading people to think otherwise than they did before. Yet human societies are built upon consensus, which makes conversions necessary. I would argue that creating moments for people to experience a familiar thing in a new way, thereby paving the way moments of conversion and consensus, is the ultimate purpose of media and art.

Inspired by the idea that literary fiction is a way to knowledge (Hemer 2012:30) and through the framework of Gilles Deleuze’s philosophy of becoming (Deleuze 1995), this installation will explore the ways in which works of fiction, and particularly speculative fiction, play with experiences that are false and unknowable in order to express and facilitate moments of seeing things in a new light. The installation would lead viewers through a multimodal experience of an excerpt from Submission, Michel Houellebecq’s work of speculative fiction, in which Houellebecq’s protagonist has one in a series of encounters with a foreign way of life that ultimately lead to his conversion to Islam. Far from a mystical experience, Houellebecq creates a banal conversion experience that achieves cognitive estrangement through physical seduction.

Context

Submission takes off with the speculative premise that the nationalist-populist National Front and the Muslim Brotherhood are the two dominant political parties in France in 2022. We follow the psychological journey of an middle-aged academic, François, as he tries to reconcile his decidedly secular lifestyle with the rising dominance of Islam in French society. At the start of the novel François’ life consists primarily of an intense personal and professional engagement with the literary works of real-life French novelist J.K. Huysmans, the casual satiation of sexual desires, a penchant for take-out food, and a generally listless attitude toward life. By the end of the novel he has converted to Islam in the pursuit of pleasure and comfort. His journey along the way is guided by materialistic and corporeal desires, which Houellebecq brings to life in rich aesthetic descriptions of trivial and sensuous materialities, evolving in parallel with his study of J.K. Huysman’s conversion to Catholicism over a century earlier. Through a pragmatic reading of Michel Houellebecq’s novel Submission, I posit that by using speculative fiction as a method, Houellebecq creates the parameters in which both his protagonist and the reader can experience the submission of women as not only a possible, but potentially a desirable, future. Throughout the reading of the text, together with François and Houellebecq, we leave behind our historical preconditions and we “become,” we create something new (Deleuze 1995:171). Although I maintain that all fiction is operational, I open for exploration whether speculative fiction is more analogous to functional code or test code in the context of Test-Driven Development (TDD): does speculative fiction serve primarily to run an alternative present or debug the future?

Literature, though not strictly executable unless exists in electronic format and cannot be accessed without running code (Galloway 2004:244), nevertheless "activates a recursive feedback loop between knowledge realized in the body through gesture, ritual, performance, posture, and enactment, and knowledge realized in the neocortex as conscious and explicit articulations” (Hayles 2008:132). Just as software code lies dormant until it is executed, so do words lie dormant on a page, or a screen, until they are read (visually, aurally, sensually) and given meaning by human comprehension. As long as a book remains closed, the words lie dormant, like a series of 0’s and 1’s waiting for the command to run. The processes of writing and reading are where meaning-making occurs, as stories influence thoughts and ideas that may over time turn into actions and new realities (Whitehead 1955). N. Katherine Hayles elaborates on the differences and similarities between book and computer programs:

“The book is like a computer program in that it is a technology designed to change the perceptual and cognitive states of a reader. The difference comes in the degree to which the two technologies can be perceived as cognitions of the writer that are stored until activated by a reader, at which point a complex transmission process takes place between writer and reader, mediated by the specificities of the book as a material medium.” (Hayles 2008:57-58).

While the words in a novel exist independent of observation, encoded in pure linguistic signs independent of the act of reading, they behave differently upon each reading as they interact with readers’ varieties of assumptions, prior knowledge, attitudes, temperaments, and environments. Similarly, the same software code may behave differently upon each execution as it runs on top of a variety of software code and platforms (Chun 2004:28).

Many have extolled the agency of literature and its power to create. Deleuze attributes literature with the power to generate new “becomings," declaring that "The ultimate aim of literature is to set free, in the delirium, this creation of a health or this invention of a people, that is, a possibility of life" (Deleuze 1997:4). The pragmatist turn in American philosophy around the turn of the twentieth century marked the beginning of a diverse legacy of philosophers who have rejected continental correlationism and anti-realism, most recently manifested in a loose “speculative realist” cohort of philosophers and artists (Galloway 2013:353), which has significance in its application to the purpose and functioning of literature. Pragmatists philosophers and artists treated literature as an experimental process generating a loop of perception, actions, and consequences for both writers and readers (Grimstad 2013:1-2) in which "each individual work has to discover anew the criteria by which its particular forms of saying become sharable” (Grimstad 2013:15). This shift in philosophical thinking blossomed in tandem with different forms of experimental writing that explored the concept of literature as a generative space of creation for both writers and readers: genres such as detective novels, horror, science fiction, fantasy, and speculative fiction (often categorized jointly under the abbreviation “sf").

Though all fiction by definition does not make a pretense of telling the truth, speculative fiction is unique in that it makes no pretensions whatsoever of dealing within the “rules” of reality in literary realist traditions. Speculative fiction alters the rules of life, the superstructures we operate within, by introducing new societies, temporal and territorial manipulation, and/or technological advancements, thereby unlocking the theoretical girds of our blocked reality and removing even the most basic assumptions that the reader brings into the reading (Fitter 1975:166). By removing all pretensions of experimenting within the bounds of reality, writers and readers of speculative fiction therefore take advantage of the medium as a catalyst the questioning fundamental points of consensus, for revealing the structures behind the status quo, and laying the ground for the potential adoption of new opinions. Many scholars have recognized the unique ability of “sf” to create fertile ground for seeing otherwise: it allows us to “see through the eyes of the other” (Gordon 2008:192); it deviates norms of reality for the writer and the reader (Zepke 2012); it can "defamliarize and restructure our experience of our own present" (Jameson 2005:286); it makes the familiar seem strange and helps construct “what might be” (Damarin 2004:53).

The world of Houellebecq’s François in bears fairly close resemblance to modern-day Paris: François rides the TGV, watches YouPorn, works on a laptop, smokes cigarettes, orders take-out sushi, and Marine Le Pen is the president of the National Front party. Without employing any grandiose reality-warping tricks, Houellebecq proceeds in the course of 256 pages to erode two of the fundamental building blocks of modern-day French society: secularism and equal rights for women. So, how does Houellebecq create an experience with the reader in which the democratic adoption of Sharia law in France seem authentic, plausible, and even desirable? Rather than jolting the narrative to a level of cognitive estrangement that by defamliarizing the mundane, Houellebecq builds the narrative on top of descriptions of the mundane, trivial, materialistic pleasures of modern consumer culture. In this way he lulls, or seduces, participants in the narrative to accept an unlikely scenario as both a possible future and a reflection on present realities.

Which opens the question: if the meaning of literature lies in the experience of it, in the process of reading and writing, then does speculative fiction operate more like functional code or test code when it is "executed"? According to Kent Beck, a well-known software developer and who outlined the principles and practices of Test-Driven Development (TDD) in his book Test-Driven Development: By Example (2002), software developers should spend at least 25-50% of their time writing test code that runs in tandem with functional code (at a ratio of about three to one). In a world saturated by software and its accompanying bugs and errors, a tremendous amount of resources is dedicated to predicting and averting points of failure. Speculative fictions serve as portenders of things to come as they weave into the imaginaries and enactments of future presents (Dourish & Bell 2014). Submission runs in reaction and in parallel to our current state of affairs, shining a light on potential points of failure to come. Therefore, in the pragmatist tradition of analyzing literature, not in terms of whether it is "true" or "accurate" but in terms of "what it does" (Wood 1996:12), I look at speculative fiction and Houellebecq's novel as a combination of functional and test code, both the mirror and the caution sign.

In an eery turn of events, Submission was published in France on January 7, 2015, the same day as the Charlie Hebdo shooting, in which Islamist terrorists killed 12 people in the magazines Paris offices. The issue of Charlie Hebdo that was published just before the massacre featured a full-cover satiric cartoon of Michel Houellebecq under the headline, "The Predictions of Wizard Houellebecq." With fatwas being issued on authors' heads and the rise of Donald Trump's presidential campaign on the platform of banning Muslims from entering the United States, Submission presents a strong case for analyzing speculative fiction as operational media.

Interactive Installation

My installation is intended to create a multimodal experience that dives into one of the scenes in Submission when we experience an alternative reality in which women have lost all autonomy and are permanently submissive to men, yet we perceive how this state of affairs could be beneficial for both men and women. The installation is meant to question the generative nature of narratives and the feedback loop between writer and reader by alternatively decoupling and reuniting images of events in the novel from their corresponding text.

First, you hold up a 3-D View-Master stereoscope to your eyes and put on a pair of headphones. The headphones are connected to a laptop with three sound files open that alternate randomly on shuffle. The stereoscope contains a reel of seven images that illustrate the events in a scene from Submission.

Participants press play to start the sound file and then look into the stereoscope at the first image. After the first track of the sound track comes to an end, participants flip the switch on the stereoscope (also known as "dropping the guillotine”). The switch is connected to an Arduino microcomputer that has been programmed to move to the next soundtrack when the stereoscope switch is flipped. Therefore, participants will listen to text that corresponds with each of the seven images that they view.

Content of images:

- Image 1: François in a seat on the TGV by himself holding a newspaper, looking at the party sitting across the aisle

- Image 2: Arab businessman in long white djellaba and a white keffiyeh sitting in front of two tables, two young girls in their teens wearing long robes and multi-colored veils sitting across the aisle from François. There are files spread out across the tables in front of the businessman. One girl is reading a Picsou comic and giggling, the other is reading the latest issue of Oops magazine. Candy bars sit on the tables in front of the girls.

- Image 3: Looking over the businessman’s shoulder. He has his emails and spreadsheets open on his computer. He is making a call on his cell phone. A side-long shot at his face shows that he is busy and stressed.

- Image 4: François tries to return to reading his newspaper

- Image 5: The two young Arab girls are giggling to each other and pointing at the copy of Picsou while the businessman looks at them with a tense smile, still on his cell phone

- Image 6: Over-the-shoulder shot of the two girls, heads together, whispering happily to each other and giggling. We see their magazines and candy littered over the table in front of them.

- Image 7: Full screen shot of François’ face, lost in thought

The disorienting feature is that participants will listen to one of three sound files. One sound files is an audio recording of the text from Submission, so the participant will listen to the text of the novel while looking at a visual illustration of the scene. One sound file is an audio recording of an excerpt from Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace in which a main character, Prince Andrei, undergoes a conversion experience that is manifested in his reactions to an oak tree that his carriage drives by on the way to and from his destination. The third sound file is an audio recording of an excerpt from J.K. Huysmans’ À Rebours in which the protagonist, Des Esseintes, expresses the failings of nature in comparison to artifice and sensually describes the attractive physicality of locomotives.

While the three textual excerpts have common themes and literary devices, such as rich imagery that defamiliarize us from familiar objects, the displacement of spiritual journeys into physical objects, elements of physical journeys through modes of man-made transportation, their pairings with the images will create three very different narrative experiences for the participants. Although the stereoscope and audio will be set up in such a way that participants have no control over the content that they experience (the images move linearly without a possibility of rewinding, the audio files are programmed to play at prescribed moments), this is only meant to highlight that the meaning of the same content lies in the participants’ experience of it.

Excerpt from Submission with corresponding images (pages 183-185):

Image 1: I found a seat by myself, with no one across from me. Image 2: On the other side of the aisle a middle-aged Arab businessman, dressed in a long white djellaba and a white keffiyeh, had spread out several files on the two tables in front of his seat. He must have been coming from Bordeaux. There were two young girls facing him, barely out of their teens — his wives, clearly — who had raided the newsstand for candy and magazines. They were excited and giggly. They wore long robes and multicolored veils. For the moment, one was absorbed in a Picsou comic, the other in the latest issue of Oops. Image 3: Across from them, the businessman looked as if he was under some serious stress. Opening his e-mail, he downloaded an attachment containing several Excel spreadsheets, and after examining these documents, he looks even more worried than before. He made a call on his cell phone. A long, hushed conversation ensued. Shot 4: It was impossible to tell what he was talking about, and I tried, without a great deal of enthusiasm, to get back to my Figaro, which covered the new regime from a real estate and luxury angle. From this point of view, the future was looking extremely bright. The subjects of the petromonarchies were more and more eager to pick up a pied-à-terre in Paris or on the Côte d’Azur, now that they knew they were dealing with a friendly country, and were outbidding the Chinese and the Russians. Business was good. Image 5: Peals of laughter: the two young Arab girls were hunched over the copy of Picsou, playing “Spot the Difference.” Looking up from his spreadsheet, the businessman gave them a pained smile of reproach. They smiled back and went on playing, now in excited whispers. He took out his cell again and another conversation ensued, just as long and confidential as the first. Image 6: Under an Islamic regime, women — at least the ones pretty enough to attract a rich husband — were able to remain children nearly their entire lives. No sooner had they put childhood behind them than they became mothers and were plunged back into a world of childish things. Their children grew up, then they became grandmothers, and so their lives went by. There were just a few years where they bought sexy underwear, exchanging the games of the nursery for those of the bedroom — which turned out to be much the same thing. Image 7: Obviously they had no autonomy, but as they say in English, fuck autonomy. I had to admit, I’d no trouble giving up all of my professional and intellectual responsibilities, it was actually a relief, and I had no desire whatsoever to be that businessman sitting on the other side of our Pro Première compartment, whose face grew more and more ashen the longer he talked on the phone, and who was obviously in some kind of deep shit. Our train had just passed Saint-Pierre-des-Corps. At least he’d have the consolation of two graceful, charming wives to distract him from the anxieties facing the exhausted businessman — and maybe he had two more wives waiting for him in Paris. If I remembered right, according to sharia law you could have up to four. What had my father had? My mother, that neurotic bitch. I shuddered at the thought. Well, she was dead now. They were both dead. I might have seen better days, but I was the only living witness to their love.

Excerpt from Huysmans’ À Rebours with corresponding images:

Image 1: To tell the truth, artifice was in Des Esseintes' philosophy the distinctive mark of human genius.

As he used to say, Nature has had her day; she has definitely and finally tired out by the sickening monotony of her landscapes and skyscapes the patience of refined temperaments. When all is said and done, what a narrow, vulgar affair it all is, like a petty shopkeeper selling one article of goods to the exclusion of all others; what a tiresome store of green fields and leafy trees, what a wearisome commonplace collection of mountains and seas!

Image 2: In fact, not one of her inventions, deemed so subtle and so wonderful, which the ingenuity of mankind cannot create; no Forest of Fontainebleau, no fairest moonlight landscape but can be reproduced by stage scenery illuminated by the electric light; no waterfall but can be imitated by the proper application of hydraulics, till there is no distinguishing the copy from the original; no mountain crag but painted pasteboard can adequately represent; no flower but well chosen silks and dainty shreds of paper can manufacture the like of!

Yes, there is no denying it, she is in her dotage and has long ago exhausted the simple-minded admiration of the true artist; the time is undoubtedly come when her productions must be superseded by art.

Image 3: Why, to take the one of all her works which is held to be the most exquisite, the one of all her creations whose beauty is by general consent deemed the most original and most perfect,--woman to wit, have not men, by their own unaided effort, manufactured a living, yet artificial organism that is every whit her match from the point of view of plastic beauty? Does there exist in this world of ours a being, conceived in the joys of fornication and brought to birth amid the pangs of motherhood, the model, the type of which is more dazzlingly, more superbly beautiful than that of the two locomotives lately adopted for service on the Northern Railroad of France?

Image 4: One, the Crampton, an adorable blonde, shrill-voiced, slender-waisted, with her glittering corset of polished brass, her supple, catlike grace, a fair and fascinating blonde, the perfection of whose charms is almost terrifying when, stiffening her muscles of steel, pouring the sweat of steam down her hot flanks, she sets revolving the puissant circle of her elegant wheels and darts forth a living thing at the head of the fast express or racing seaside special!

Image 5: The other, the Engerth, a massively built, dark-browed brunette, of harsh, hoarse-toned utterance, with thick-set loins, panoplied in armour-plating of sheet iron, a giantess with dishevelled mane of black eddying smoke, with her six pairs of low, coupled wheels, what overwhelming power when, shaking the very earth, she takes in tow, slowly, deliberately, the ponderous train of goods waggons.

Image 6: Of a certainty, among women, frail, fair-skinned beauties or majestic, brown-locked charmers, no such consummate types of dainty slimness and of terrifying force are to be found. Without fear of contradiction may we say: man has done, in his province, as well as the God in whom he believes.

Image 7: Thoughts like these would come to Des Esseintes at times when the breeze carried to his ears the far-off whistle of the baby railroad that plies shuttlewise backwards and forwards between Paris and Sceaux. His house was within a twenty minutes' walk or so of the station of Fontenay, but the height at which it stood and its isolated situation left it entirely unaffected by the noise and turmoil of the vile hordes that are inevitably attracted on Sundays by the neighbourhood of a railway station.

Excerpt from Tolstoy’s War and Peace with corresponding images (pages 419-420):

Image 1: At the side of the road stood an oak. Probably ten times older than the birches of the woods, it was ten times as thick and twice as tall as any birch. It was an enormous oak, twice the span of a man’s arm in girth, with some limbs broken off long ago, and broken bark covered with old scars. With its huge, gnarled, ungainly, unsymmetrically spread arms and fingers, it stood, old, angry, scornful, and ugly, amidst the smiling birches. It alone did not want to submit to the charm of spring and did not want to see either the springtime or the sun. Image 2: “Spring, and love, and happiness!” the oak seemed to say. “And how is it you’re not bored with the same, stupid, senseless deception! Always the same, and always a deception! There is no spring, no sun, no happiness. Look, there sit those smothered, dead fir tress, always the same; look at me spreading my broken, flayed fingers wherever they grow — from my back, from my sides. As they’ve grown, so I stand, and I don’t believe in your hopes and deceptions." Image 3: Prince Andrei turned several times to look at this oak as he drove through the woods, as if he expected something from it. There were flowers and grass beneath the oak as well, but it stood among them in the same way, scowling, motionless, ugly, and stubborn. Image 4: “Yes, it’s right, a thousand times right, this oak,” thought Prince Andrei. “Let others, the young ones, succumb afresh to this deception, but we know life — our life is over!” A whole new series of thoughts in connection with the oak, hopeless but sadly pleasant, emerged in Prince Andrei’s soul. During this journey it was as if he again thought over his whole life and reached the same old comforting and hopeless conclusion, that there was no need for him to start anything, that he had to live out his life without doing evil, without anxiety, and without wishing for anything. Image 5: “Yes, here in this woods,was that oak that I agreed with,” thought Prince Andrei. “But where is it?” he thought again, looking at the left side of the road, and, not knowing it himself, not recognizing it, he admired the very oak he was looking for. The old oak, quite transformed, spreading out a canopy of juicy, dark greenery, basked, barely swaying, in the ray of the evening sun. Of the gnarled fingers, the scars, the old grief and mistrust — nothing could be seen. Juicy green leaves without branches broke through the stiff, hundred-year-old bark, and it was impossible to believe that this old fellow had produced them. Image 6: “Yes it’s the same oak,” thought Prince Andrei, and suddenly a causeless springtime feeling of joy and renewal came over him. All the best moments of his life suddenly recalled themselves to him at the same time. Austerlitz with the lofty sky, and the dead, reproachful face of his wife, and Pierre on the ferry, and a girl excited by the beauty of the night, and that night itself, and the moon — all of it suddenly recalled itself to him. Image 7: “No, life isn’t over at the age of thirty-one,” Prince Andrei suddenly decided definitively, immutably. “It’s not enough that I know all that’s in me, everyone else must know it, too: Pierre, and that girl who wanted to fly into the sky, everyone must know me, so that my life is not only for myself; so that they don’t live like that girl, independently of my life, but so that it is reflected in everyone, and they all live together with me!"

References

Chun, W. (2004). "On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge”, in Grey Room 18, pp. 26–51 http://www.brown.edu/Departments/MCM/people/chun/papers/software.pdf

Damarin, S. (2004). "Chapter Three: Required Reading: Feminist Sci-Fi and Post-Millennial Curriculum", in Counterpoints vol. 158, pp. 51-73

Deleuze, G. (1995). Negotiations, 1972–1990. New York: Columbia University Press

(1997). Essays critical and clinical. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

(1994). Difference and Repetition. Trans. Patton, P. New York, Columbia University Press

Eizykman, B. (1975). "On Science Fiction", Trans. Fitting, P. in Science Fiction Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 164-166

Bahti, T. (1993). "Review of Narrative Crossings: Theory and Pragmatics of Prose Fiction. By Alexander Gelley", in Comparative Literature vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 177-180

Dourish, P. and Bell, G. (2014). "Resistance is Futile": Reading Science Fiction Alongside Ubiquitous Computing.” in Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 18, 4, pp. 769-778.

Galloway, A. (2004). Protocol: How Control Exists After Decentralization. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

(2013) "The Poverty of Philosophy: Realism and Post-Fordism", in Critical Inquiry, vol. 39, no. 2 pp. 347-366

Gordon, J. "Gazing across the Abyss: The Amborg Gaze in Sheri S. Tepper's "Six Moon Dance" Author(s): Joan Gordon Source: Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 35, No. 2, On Animals and Science Fiction (Jul., 2008), pp. 189-206 Published by: SF-TH Inc Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25475138 Accessed: 13-04-2016 13:24 UTC

Grimstad, P. (2013). Experience and Experimental Writing: Literary Pragmatism from Emerson to the Jameses. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Hayles, N. K. (2008). Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame

Hemer, O. (2012). Fiction and Truth in Transition: Writing the present past in South Africa and Argentina. Zürich: LIT VERLAG GmbH & Co. KG Wien

Houellebecq, M. (2015). Submission: A Novel. Trans. Stein, L. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Jameson, F. (2005). Archaeologies of the future, the desire called utopia and other science fictions. London: Verso

Whitehead, A. (1955). Adventures of Ideas. A Mentor Book.

Wood, B. (1996). "William S. Burroughs and the Language of Cyberpunk”, in Science Fiction Studies vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 11-26

Zepke, S. (2012). "Beyond cognitive estrangement: The future of science fiction cinema”, in NECSUS: European Journal of Media Studies http://www.necsus-ejms.org/beyond-cognitive-estrangement-the-future-of-science-fiction-cinema/