Difference between revisions of "Exe0.2 Geraldine Juárez"

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

A critique of the Google Cultural Institute where their motivations are interpreted as merely colonialist would be misleading and counterproductive. It is not their goal to slave and exploit whole populations and its resources in order to impose a new ideology and civilise barbarians in the same sense and way that European countries did during the Colonization. Additionally, it would be unfair and disrespectful to all those who still have to deal with the endless effects of Colonization, that have exacerbated with the expansion of economic globalisation. | A critique of the Google Cultural Institute where their motivations are interpreted as merely colonialist would be misleading and counterproductive. It is not their goal to slave and exploit whole populations and its resources in order to impose a new ideology and civilise barbarians in the same sense and way that European countries did during the Colonization. Additionally, it would be unfair and disrespectful to all those who still have to deal with the endless effects of Colonization, that have exacerbated with the expansion of economic globalisation. | ||

The conflation of technology and science (technoscience) that has produced the knowledge to create such an entity as Google and its derivatives, such as the Cultural Institute, together with the scale of its impact on a society where information technology is one of the dominant form of technology – but not the only one -, makes ''technocolonialism'' a more accurate term to describe Google's cultural interventions from my perspective. But '''what is ''technocolonialism''?'''. | The conflation of technology and science (technoscience) that has produced the knowledge to create such an entity as Google and its derivatives, such as the Cultural Institute, together with the scale of its impact on a society where information technology is one of the dominant form of technology – but not the only one -, makes ''technocolonialism'' a more accurate term to describe Google's cultural interventions from my perspective. But '''what is ''technocolonialism''?'''. | ||

The main purpose of this text is to produce a defintion of ''technocolonialism'', using the Google Cultural Institute as case study/sample/object. | |||

====Technocolonialism: a definition==== | ====Technocolonialism: a definition==== | ||

* How do you produce a defintion? | |||

To my knowledge, there is no official definition of technocolonialism, but it is important to understand it as a continuation of the idea of Enlightenment that gave birth to the impulse to collect, organise and manage information in the 19th century. My use of this term aims to emphasize and situate contemporary accumulation and management of information and data within a technoscientific landscape driven by “profit above else” as a “logical extension of the surplus value accumulated through colonialism and slavery.”<ref>http://www.openhumanitiespress.org/books/titles/art-in-the-anthropocene/ Davis, Heather & Turpin, Etienne, eds. Art in the Anthropocene (London: Open Humanities Press. 2015), 7</ref> | To my knowledge, there is no official definition of technocolonialism, but it is important to understand it as a continuation of the idea of Enlightenment that gave birth to the impulse to collect, organise and manage information in the 19th century. My use of this term aims to emphasize and situate contemporary accumulation and management of information and data within a technoscientific landscape driven by “profit above else” as a “logical extension of the surplus value accumulated through colonialism and slavery.”<ref>http://www.openhumanitiespress.org/books/titles/art-in-the-anthropocene/ Davis, Heather & Turpin, Etienne, eds. Art in the Anthropocene (London: Open Humanities Press. 2015), 7</ref> | ||

Unlike in colonial times, in contemporary technocolonialism the important narrative is not the supremacy of a specific human culture. Technological culture is the saviour. It doesn’t matter if the culture is Muslim, French or Mayan, the goal is to have the best technologies to turn it into data, rank it, produce ''content'' from it and create experiences that can be ''monetized''. | |||

It only makes sense that Google, a company with a mission of to organise the world’s information for profit, found ideal partners in the very institutions that were previously in charge of organising the world’s knowledge. But as I pointed out before, it is paradoxical that the Google Cultural Institute is dedicated to collect information from museums created under Colonialism in order to elevate a certain culture and way of seeing the world above others. Today we know and are able to challenge the dominant narratives around cultural heritage, because these institutions have an actual record in history and not only a story produced for the ‘about’ section of a website, like in the case of the Google Cultural Institute. | |||

“What museums should perhaps do is make visitors aware that this is not the only way of seeing things. That the museum – the installation, the arrangement, the collection – has a history, and that it also has an ideological baggage”[8]. But the Google Cultural Institute is not a museum, it is a database with an interface that enables to browse cultural content. Unlike the ''prestigious'' museums it collaborates with, it lacks a history situated in a specific cultural discourse. It is about fine art, world wonders and historical moments in a ''general sense''. The Google Cultural Institute has a clear corporate and philanthropic mission but it lacks a point of view and a defined position towards the cultural material that it handles. This is not surprising since Google has always avoided to take a stand, it is all techno-determinism and the noble mission of organising the world’s information to make the world better. But “brokering and hoarding information are a dangerous form of techno-colonialism.”[9] | |||

Searching for a cultural narrative beyond the Californian ideology, the Alphabet's search engine has been looking for different cultural narratives to insert their philanthropic services in the history of information science beyond Silicon Valley. After all, they understand that “ownership over the historical narratives and their material correlates becomes a tool for demonstrating and realizing economic claims”.[10] | |||

====Relevant concepts & differences with==== | ====Relevant concepts & differences with==== | ||

Revision as of 23:38, 17 April 2016

Geraldine Juárez - Artist

Master in Fine Arts / Valand Academy

Portions of this abstract are part of previous texts such as "Technocolonial Intergalactic" (forthcoming Intercalations 3) and A pre-emptive history of the Google Cultural Institute (2016) (forthcoming Constant)

- Execution as deterritorialization

Introduction

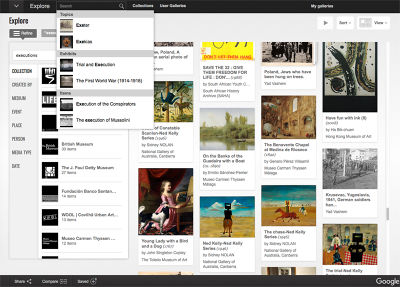

The Google Cultural Institute is a complex subject of interest since it reflects the colonial impulses embedded in the scientific and economic desires that formed the very collections which the Google Cultural Institute now mediates and accumulates in its database.

A critique of the Google Cultural Institute where their motivations are interpreted as merely colonialist would be misleading and counterproductive. It is not their goal to slave and exploit whole populations and its resources in order to impose a new ideology and civilise barbarians in the same sense and way that European countries did during the Colonization. Additionally, it would be unfair and disrespectful to all those who still have to deal with the endless effects of Colonization, that have exacerbated with the expansion of economic globalisation.

The conflation of technology and science (technoscience) that has produced the knowledge to create such an entity as Google and its derivatives, such as the Cultural Institute, together with the scale of its impact on a society where information technology is one of the dominant form of technology – but not the only one -, makes technocolonialism a more accurate term to describe Google's cultural interventions from my perspective. But what is technocolonialism?.

The main purpose of this text is to produce a defintion of technocolonialism, using the Google Cultural Institute as case study/sample/object.

Technocolonialism: a definition

* How do you produce a defintion?

To my knowledge, there is no official definition of technocolonialism, but it is important to understand it as a continuation of the idea of Enlightenment that gave birth to the impulse to collect, organise and manage information in the 19th century. My use of this term aims to emphasize and situate contemporary accumulation and management of information and data within a technoscientific landscape driven by “profit above else” as a “logical extension of the surplus value accumulated through colonialism and slavery.”[1]

Unlike in colonial times, in contemporary technocolonialism the important narrative is not the supremacy of a specific human culture. Technological culture is the saviour. It doesn’t matter if the culture is Muslim, French or Mayan, the goal is to have the best technologies to turn it into data, rank it, produce content from it and create experiences that can be monetized.

It only makes sense that Google, a company with a mission of to organise the world’s information for profit, found ideal partners in the very institutions that were previously in charge of organising the world’s knowledge. But as I pointed out before, it is paradoxical that the Google Cultural Institute is dedicated to collect information from museums created under Colonialism in order to elevate a certain culture and way of seeing the world above others. Today we know and are able to challenge the dominant narratives around cultural heritage, because these institutions have an actual record in history and not only a story produced for the ‘about’ section of a website, like in the case of the Google Cultural Institute.

“What museums should perhaps do is make visitors aware that this is not the only way of seeing things. That the museum – the installation, the arrangement, the collection – has a history, and that it also has an ideological baggage”[8]. But the Google Cultural Institute is not a museum, it is a database with an interface that enables to browse cultural content. Unlike the prestigious museums it collaborates with, it lacks a history situated in a specific cultural discourse. It is about fine art, world wonders and historical moments in a general sense. The Google Cultural Institute has a clear corporate and philanthropic mission but it lacks a point of view and a defined position towards the cultural material that it handles. This is not surprising since Google has always avoided to take a stand, it is all techno-determinism and the noble mission of organising the world’s information to make the world better. But “brokering and hoarding information are a dangerous form of techno-colonialism.”[9]

Searching for a cultural narrative beyond the Californian ideology, the Alphabet's search engine has been looking for different cultural narratives to insert their philanthropic services in the history of information science beyond Silicon Valley. After all, they understand that “ownership over the historical narratives and their material correlates becomes a tool for demonstrating and realizing economic claims”.[10]

Relevant concepts & differences with

What is the relation as well as difference of technocolonialism with:

- Management

- Solutionism

- Spectacle

- Thesis 24: But the spectacle is not the necessary product of technical development seen as a natural development. The society of the spectacle is on the contrary the form which chooses its own technical content. [2]

References

- ↑ http://www.openhumanitiespress.org/books/titles/art-in-the-anthropocene/ Davis, Heather & Turpin, Etienne, eds. Art in the Anthropocene (London: Open Humanities Press. 2015), 7

- ↑ http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/display/77 From The Society of the Spectacle by Guy-Ernest Debord